Experience

Data Scientist @ Accenture

Milan, Jun 2024 - Today

Data Scientist @ Versace

Milan, Sept 2023 - Jun 2024

Data Science Intern @ Google

London, Aug - Nov 2022

Causal inference

Causal inference is the field of statistics and ML which aims to determine whether two or more

variables in a system are linked one to another by cause-effect relationships. Having an

understanding of the latter unlocks the possibility to produce interventional and, ultimately,

counterfactual scenarios that didn`t happen in reality (Pearl, Causality, 2009; Pearl and Mackenzie,

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect, 2018).

Assume you have a Structural Causal Model (SCM), which is built on a causal

graph and causal mechanisms, namely either functional forms which describe the generative process of nodes given their progenitors

or stochastic distributions for root nodes. In practice, producing interventional scenarios means responding to a question

of the kind of 'What would happen if ..' (in the past if dealing with counterfactuals) by intervening on a node,

propagating changes through its successors, possibly resulting in a different system outcome. This makes

causal inference key in those industries where there are considerable risks in providing certain treatments, as for

healthcare and finance.

Despite being an extremely powerful tool, real-world data is often imperfect, subject to biases,

unmeasured confounding, and structural complexity, leading to possible threats to the reliability

and robustness to this class of methods. Whether the causal graph is obtained from causal discovery, given the data at hand, or is defined

via domain knowledge only, ensuring the reliability of the framework starts with the validation of the graph, meaning it is

informative for the system and is representative for the data at hand.

DoWhy is the python causal inference library I used

to build an inference framework targeting the cause-effect relationship between customer satisfaction and churn behaviour.

In such a problem, where satisfaction is one of the most subjective data, ensuring a valid graph is certainly challenging.

Probabilistic regression

Traditionally, when dealing with a regression problem, the typical task is to provide a point estimate for each input, where a plethora of models is available,

from standard linear regression to tree-based algorithms. However, when dealing with real-world data, these point prediction hide an important aspect, which is

uncertainty.

To address the estimation of the latter, Duan et al. [2019] developed the Natural Gradient Boosting

algorithm (NGBoost), which aims to provide probabilistic prediction via gradient boosting. Having knowledge of the uncertainty in a regression model, enables better

decision-making, which can be crucial when dealing with medical cases for instance. Their code is publicly available as a python library

(github repo, from which the gif on the left was taken).

During my internship, I had the chance to work with this kind of algorithms, developing extensions useful to the project I was assigned to.

Deepfakes

In recent year the diffusion of Machine-Learning had an incredible boost, reaching almost everyone: a well-known example are the social media

tools which allow to swap your face with someone or something else. These are an example of deepfakes, which in general generate realistic

synthetic images or masks representing our target in a new environment. Despite being funny when used to swap your face with your doggo,

deepfakes pose a real thread as reported in numerous episodes, not limited to

these.

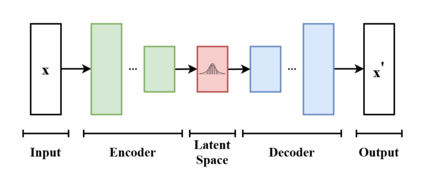

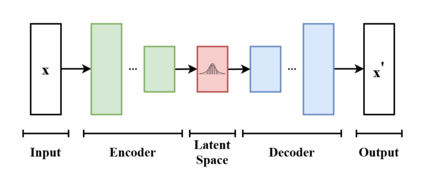

The substance behind these algorithms are

Variational AutoEncoders,

represented in this image.

In this project, done in collaboration with the NCC group, we analyse possible ways of recognizing deepfakes, mitigating the possible risks

of fraud.

Online at

NCC group webpage, 2020

Faceswap tool

Research

PhD Thesis work

The development of robust inference frameworks is crucial to reliably improve our understanding of the standard cosmological model,

shedding light to open problems it currently suffers of. However, the increasing complexity of current analyses urged the need for

optimal data compression algorithms and alternative simulation-based Bayesian approaches, which development was boosted by Machine

Learning advances. My thesis work focuses on testing and applying these techniques to problems in the field of

gravitational waves and the Lyman-α forest, extended below.

Simulation-based inference and data compression applied to cosmological problems, Published on UCL Discovery, 2024

Quantifying information in compressed analyses of BAO

Over the last decades, the ΛCDM model

affirmed itself as a successful theory, able to descibe multiple cosmological

observations while modelling the Universe's dynamics and structure with only six parameters.

With the advance of technology and instrumental power, there has been a boost in the quality of the data, tightening the constraints

on these parameters, urging for testing standard inference analyses against systematics and loss of information.

Amongst the diverse probes that can be used to constrain the ΛCDM parameters, there is the

Baryonic Acoustic Oscillations (BAO) scale,

which is detectable over

different tracers

of the matter density field. Among them, there is the Lyman-α Forest, which is a sequence of absorption lines in high-redshift quasar

spectra, caused by the neutral hydrogen distributed along the line of sight, between the quasar and the observer.

Check out this animation!

BAO produce a distinct peak feature in the correlation functions, as in the plot, which we can robustly use to probe the cosmological model.

Standard analyses of the Lyman-α correlation functions only consider the information carried by that peak. We conducted

two case studies.

The first one addresses whether this compression is sufficient to capture all the relevant cosmological information carried by

these functions, while performing a full shape analysis.

Direct cosmological inference from three-dimensional correlations of the Lyman-α forest, Published on MNRAS, 2022

In the second study, we apply score compression on realistic Lyα correlation functions and explore some of its

outcomes, in cluding reliable covariance matrix estimation.

Optimal data compression for Lyman-α forest cosmology, Published on MNRAS, 2023

Simulation-based inference applied to gravitational waves

When constraining the values of the ΛCDM parameters from observations, we rely on traditional Bayesian inference, which requires

the likelihood function to be analytically known. The likelihood is the probability of the data given a parameter value and the larger

the complexity of the problem the harder it is to compute this quantity accurately and fastly. In the case in which the likelihood

evaluation is significantly harder to compute, we can completely bypass it by performing the inference in a framework in which the

likelihood is never explicitly calculated, but instead fit using forward simulations of the data. This is simulation-based inference.

A particular example is density-estimation SBI, in which a neural density estimators (NDEs) is trained to fit the joint parameter-data

space. For more details, check out this paper!

Gravitational waves have proven to be powerful probes for tracing the evolution of the Universe expansion rate, but their constraining

power is reliable provided the analysis is free from systematics, which could arise from selection effects. In the traditional Bayesian

framework, accounting for these effects in the likelihood requires potentially costly and/or inaccurate processes.

In this paper, we use density-estimation SBI, coupled to neural-network-based data compression, to infer cosmological parameters from a

bayesian hierarchical model. We demonstrate that SBI yields statistically unbiased estimates of the cosmological parameters of interest.

Unbiased likelihood-free inference of the Hubble constant

from light standard sirens, Published on Physical Review D, 2021

Gaussian Processes

If case you don't know it already, our Universe is undergoing a phase of accelerated expansion! The physical mechanism that is causing it

still poses an open question and we generarically refer to it as Dark Energy. According to the ΛCDM model mentioned above, this is

driven by Einstein's Cosmological Constant Λ, which still raises theoretical questions that are far from clear. This, together with some

tensions between different probes, largely motivated the investigation of alternative models.

Theory provides a vast amount of Dark Energy models, but as of now there is no reason why you should prefer one alternative model over the other.

For this reason, we wish to place a constraint on Dark Energy in a model independent way. In particular, the dynamical contribution of the Dark

Energy to the Universe expansion is encoded into its equation of state. Hence, we wish to treat it as a free a function of time and

infer it from data in a non-parametric way. In this paper, we reconstructed the DE equation of state

by assuming an underlying gaussian process, fitting discrete inferred points.

Reconstruction of the Dark Energy equation of state from latest data: the impact of theoretical priors, Published on JCAP, 2019

Non-parametric reconstruction of cosmological functions, Master Thesis work (2018)